After a long six weeks of Spring Training, Opening Day can sometimes resemble a playoff game. Hitters swing at pitches they’d normally spit on. Amped up pitchers might spike a few pitches into the dirt. When you drop a pitch timer into this type of setting, the game can speed up quickly enough to put players on tilt.

This frenetic Opening Day environment was built for Zack Greinke, who has no problem slowing the game down. His curveball can slow things all the way down to 72 mph, in fact. As other pitchers felt the rush of the pitch clock and its potential to tempt a pitcher to “just get a fastball over the plate,” Greinke found a different gear to prey on the Opening Day energy of the Twins lineup he faced. Greinke went 5.1 innings, giving up two earned runs and striking out four. The line may not be remarkable, but Greinke’s approach was.

Not just one of 162

For context, let’s look at a few other representative examples from Opening Day. Phillies pitchers, in an 11-7 loss, had trouble slowing the game down. J.T. Realmuto tried, but he couldn’t find a reliable mechanism to stop the action for long enough or often enough to keep one bad pitch from snowballing into several bad pitches. A deep breath can help prevent that from happening, but according to Realmuto, there’s no time for that now:

With the pitch clock, you can’t ever slow the pitcher down. It’s crazy. Once an offense gets rolling and the pitcher gets on the ropes a little bit, it’s really hard. You have to make a pitch quickly to get an out. Because momentum is going to be huge now with how fast things happen and the pitcher not being able to get a breath in.

James Karinchak also cited the “deep breath” as key to preventing snowballing, after an opening night where he misfired a few times to the backstop in an inning that got away from him. In Karinchak’s second outing on Saturday, Seattle fans targeted him with a pitch clock countdown to keep the pressure on.

When Zack Greinke needed a breath, though, he just stepped off the rubber.

With this post, I’ll focus on Greinke’s navigation of 2.5 trips through the Twins lineup and what made it so fun to watch. Before we get to the the first pitch, I’ll introduce the hitters he faced and a few new tweaks Greinke’s made to his pitch mix.

Let’s meet the Twins

I’ll start with a CliffsNotes summary of the Twins lineup, which includes some characters. There are the stars - Carlos Correa and Byron Buxton. You’ll also see a variety of looks in the box (from 6’5”, 250 lb. Joey Gallo to 6’0”, 160 lb. Nick Gordon).

This lineup also includes a variety of approaches, from aggressive (Jose Miranda) to less aggressive (Christian Vázquez). In between lies Michael A. Taylor, who (for one pitch) will pretend he’s not interested before jumping into swing mode.

Some of these Twins like to ambush breaking balls more than others. Trevor Larnach eats fastballs for lunch but doesn’t seem to like anything soft. Max Kepler leads off, and he sometimes appears to sit soft1.

So there you have it - an incomplete, unsubstantiated advance scouting report on the lineup Greinke is about to face. How would you pitch to such a group? Well, it would depend on what you’re working with as a starting pitcher. If you’re Zack Greinke, the options are numerous.

What does Greinke throw in 2023?

Someone could write an entire article on the evolution of Zack Greinke’s pitch mix over the past decade, but I’m more interested in what he’s got right now. And what he has right now is actually significantly different from the mix he ended 2022 with. A quick inventory:

Four-seam fastball (90-92 mph)

Two-seam fastball (90-92)

Power changeup (86-88)

Cutter (85-88)

Slider/Sweeper (78-83)

Curveball (72-76)

The two-seam fastball is something he added this offseason. Even with it, Greinke’s velocity is light - so the secondary pitches have to work. The slider is also new and it should help. As we walk through Greinke’s 2.5 trips through the order, I’ll cover these new pitches as Greinke throws them.

Let’s dive in.

The first fastball

To open the Royals 2023 season, Greinke tries a backdoor slider (78 mph) to steal strike one on Max Kepler. Greinke hangs this breaking ball just enough to get Kepler to ambush and get underneath it. Kepler flies out to center field. 1 pitch, 1 out.

Correa is next up. Greinke pulls ahead to 2-2 without throwing one fastball (the sequence goes: curveball, slider, cutter, curveball). To put Correa away, Greinke tries a surprise heater ‘in.’ I say “surprise” here because that’s the only reason I can think of to go down-and-in on Correa with a 2-strike, 91 mph four-seam fastball - this pitch probably would’ve needed to be perfectly placed to work. Greinke misses over the plate, though, and Correa tags it (112 mph) for a single to left field:

Goodbye fastball

And that’s where Greinke decides to slow things down. He starts by abandoning the fastball; he only needed to see one to decide to put it away. He’ll use it selectively, sure. But 14 out of the next 15 pitches are either the cutter, the slider, the curveball, or the power-changeup.

Greinke’s new “primary pitch” is a big 72-76 mph curveball that gives you plenty of time to think and fidget before it reaches the plate. For a hitter who’s excited to prove something on Opening Day, it might feel like it comes in at 50 mph.

Byron Buxton is next up, and he doesn’t need to prove anything. After seeing one Greinke curveball, he flips the next pitch (also a curveball) to left field for a base hit.

Buxton’s single sets up an RBI opportunity for Trevor Larnach in his first 2023 at-bat, likely adding to Larnach’s Opening Day buzz. Larnach, after taking an 0-0 slider for a ball, watches this 72 mph curveball float in for strike one. Larnach tosses Greinke a nod and an “okay, I see you” look:

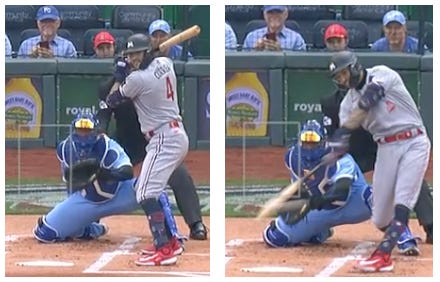

Larnach looks like he wants a fastball SO BADLY, but Greinke continues to toy with him. The next pitch is an 88 mph changeup that Larnach takes a huge cut at but tips, pushing the count to 1-2. The next pitch is a 74 mph curveball, and Larnach swings so hard at it that his bottom hand comes off the bat:

Just like that, Greinke has his first 2023 strikeout. And he didn’t need one fastball to get it.

Spin, spin, spin

Next comes Jose Miranda, who also seems to be filled with Opening Day energy. He swings at this 0-0 slider that was never a strike:

Whoa. That was a 2-strike swing at an 0-0 pitch. This is a new “sweeper” that Greinke developed in the offseason. Greinke liked the reaction (who wouldn’t) and goes right back to that pitch again, again, and again. After falling behind 0-2, though, Miranda has seen enough sweepers to show some restraint and works a walk.

Miranda’s walk sets the table for Nick Gordon, who might also be a little excited for his first 2023 at-bat. Greinke slows things down on Gordon with a curveball and one of those new sweepers to get a rollover groundball out to end the first inning.

Here’s the first inning pitch count summary: 8 sliders, 6 curveballs, 2 cutters, 2 fastballs, 1 changeup.

A Gallo-sized hole

I think there are two reasons a fastball-less Greinke might throw you a fastball. The first one is that your swing has such a big fastball hole that 89 mph, if placed in that hole, is enough velocity to pose a problem. Joey Gallo has one of these holes.

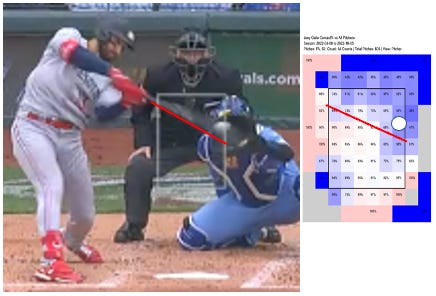

Pitchers who can spot a fastball above Gallo’s barrel (up and away from him) are safe from danger. The heatmap below shows Gallo’s contact rate against fastballs (blue areas come with a lot of swing and miss). Greinke puts a heater right where Gallo doesn’t often connect to pull ahead 0-1 on him, though Gallo will reach on the next pitch via a “new shift” ground ball error:

The other reason a fastball-less Greinke might throw you a fastball is that he doesn’t think you’re that good. Greinke, in addition to being a pitcher, is an evaluator. He speaks openly on what is good and what is bad2. For example, here’s what he had to say after this start:

Today I used my two-seam a lot more than my four-seam because my four-seam wasn’t as good as my two-seam.

To this point, we’ve seen one four-seamer and one two-seamer. To open his first matchup with the Twins 9-hole hitter (Michael A. Taylor), someone who Greinke may view as “not good,” he uses his second two-seam fastball of the day:

This is a really nice pitch. While Greinke’s cutter and his new sweeper both pull hitters off of the plate, this run-back two-seamer does the opposite. Right-handed hitters expect it to do what those other pitches do (break further away from the plate). When it starts turning back over the outside edge, most hitters have already given up. It’s a “freeze” pitch, and Greinke will introduce it selectively (and more freely to the “not good” hitters).

Greinke pours on the disrespect to Taylor with a four-seamer to follow up that pitch. Taylor fouls it off and then gets rung up on a check-swing (that wasn’t a swing) on an 0-2 sweeper.

Curveball attack

As Greinke finishes the bottom of the Twins order and begins winding through the top of it a second time, the curveball remains his go-to pitch in typical fastball counts.

He uses the curveball to steal early strikes against Christian Vázquez, Max Kepler, and Trevor Larnach (again). Greinke appears to have read his advance scouting report on Vázquez, which would’ve said something like: “Christian Vázquez saw 22 first-pitch curveballs in the zone last year and only swung at two of them.” That tidbit becomes a free strike for Greinke.

The 1-0 curveball Larnach sees in his second at-bat is a copy of the same pitch he saw (in the same count) in his first at-bat. His reaction is also the same. Another nod of recognition at Greinke:

Larnach will nod and stare, but he will not swing at a Greinke curveball (not yet, at least). He goes down looking at one to end his second at-bat.

Correa treatment

Carlos Correa is what Greinke might term a “good” hitter, so in the midst of all the curveball-ing he’s doing to everyone else, he gives Correa a different look. You could call it nibbling, and you could call it changing speeds. Here’s how Greinke starts Correa in the 4th inning:

Cutter (86 mph)

Changeup (88)

“Freeze” Two-seamer (91)

Slider/Sweeper (81)

After waving and missing at the first slider, Correa looks out to center field. I assume he’s looking for the radar gun reading and wondering what pitch he just missed by a foot:

Yes, that was the new “sweeper.” Greinke keeps throttling back and forward; another 81 mph sweeper is taken for a ball, and with a 3-2 count, Correa gets jammed by an 87 mph cutter and flies out to right field.

End of the line

The reason I love watching this version of Greinke is not so much that he can make so many different pitches and approaches work for him. It’s that, for any approach he chooses, his execution of it needs to be perfect. And it usually is. As he closes out the 4th inning, though, he hangs a two-strike curveball to Nick Gordon. Greinke’s mistake turns into a line drive out, so no harm done there; but Greinke clearly didn’t like it:

Gordon’s swing kicks off a change in approach by a few frustrated Twins hitters. They’re tired of the curveball! Michael A. Taylor sits back on a 1-0 get-me-over and drops it into left field. Kepler ambushes another one 0-0 and fouls it off.

Larnach, when he comes up next in the 6th inning, gets three in a row. He takes the first (ball), fouls the next one off. If he can just wait a little longer…

Larnach does wait a hair longer on the next pitch and lines the third consecutive curveball he sees to center field. That swing drives in Byron Buxton to put the Twins up 1-0.

Wait - how did Buxton get to third? Well, Greinke tried a special non-curveball approach on him as well. After jumping ahead of Buxton 0-2 with two well-executed teaser changeups, Greinke tried this sequence:

0-2 “freeze” two-seamer - a ball wide

1-2 chase sweeper that Buxton’s body wanted to swing at, but his hands did not

2-2 “freeze” two-seamer (set up by the previous sweeper)

Here are the 0-2 and 2-2 two-seamers side by side:

This is the margin for error that Greinke has in 2023. He can’t miss a fastball target by the width of a baseball. The 0-2 is a bit wide, and the 2-2 catches a little too much of the plate to convince Buxton to give up on it. Buxton laces that one into the gap in right-center for a triple.

If you were wondering how Zack Greinke, the pitcher with the lowest strikeout rate (12.5%) of any pitcher to throw 100 innings last year, would succeed in the face of hitter-friendly rules changes, this start is that blueprint. He developed two new pitches in the offseason; he knew the hitters he was facing; he went with what was working.

When things sped up on Greinke, he did something I haven’t seen other pitchers do this year - he just stepped off the mound. His final pitch mix looks like something that we might see copied across the league several years from now, with the way breaking ball use is trending: 20 fastballs in 80 pitches, and three different types of breaking balls. Greinke’s always one step ahead, but he’s not in a hurry.

The act of intentionally ignoring fastballs and looking for a hittable breaking ball in the strike zone.

Additional examples of Greinke’s evaluation work:

Q: What type of challenges does the Yankees’ lineup present (in the 2019 playoffs)?

A: “A lot of good hitters. It’s tough[er] to get good hitters out than not as good hitters.’’

A: “I like it a lot because I believe in it. All those number things. Especially because in Houston, they would call guys up that weren’t even good prospects. And they’d say, ‘This guy’s going to be good because his pitches do this.’ And the pitcher ended up being good.”

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F24fc095b-7fe3-4b44-a042-a40a8772bb20_187x140.gif)

![[crop output image] [crop output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0b115451-8949-4cd1-a58b-ea5a6b265195_280x210.gif)

![[crop output image] [crop output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3fc4ac25-3d97-46a9-8ffe-b7f572f7e660_228x171.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7fa018c6-00b3-432c-8625-603995e9244c_328x246.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9969a8c8-9578-4904-9a00-eada2fce3593_271x203.gif)

My new favorite newsletter. Thanks for scratching a unique baseball itch, Noah.

When you note Vazquez' reluctance (refusal?) to swing at first pitch curves in the zone - how sticky is an insight like that? Has that followed him his whole career? Is that part of a broader approach (first pitch passivity)? Very curious for any additional insight there!