There’s some Spring Training buzz going around on catcher back-picks. The consensus? We’re going to see more of them.

Braves’ pitcher Ian Anderson (per Dave O’Brien):

I think (back-picks) and pitchouts are going to be back in the game. I feel like there used to be certain things you had to be able to do before you could pitch in the big leagues, like hold the ball, pick off, pitch out. And then that completely went away. Now I think it’s coming back.

Travis d’Arnaud (in the same O’Brien story on back-picks):

And I don’t think many people back-picked last year at all, so I don’t know if people are looking for it or game-planning for it. So I think it’ll be a weapon, for sure.

Cardinals manager Oliver Marmol on Willson Contreras last week:

With the disengagement rules, there’s strategy around guys taking bigger leads and us having a guy who can back-pick really well. He’s one of the best at it, and that should keep guys from stretching out their primary and secondary [leads]. I think it’ll play a big part.

And finally, Gabe Kapler commenting on a “rocket ship” back-pick throw Joey Bart made on Tuesday:

As you can see, we’re emphasizing back-picks, and one reason is because it’s one of the few levers we can pull to control the running game with the disengagement rule.

On the one hand, it’s Spring Training - these stories and quotes fill a void. But there also might be something here. What’s the exact tie between the rule changes and this anticipated back-pick surge; and is it worth asking how the play can be best executed? Before addressing those questions, I’ll start with a quick overview.

What are back-picks?

Back-picks are throws made by a catcher to any base that are “behind” the runner (not thrown to a base a runner is trying to advance to). They look like this:

That one was game winner. Not a lot went well for the Nationals in 2022, but Kiebert Ruiz did go on a brief back-pick spree to provide a few highlight moments. Back-picks like this one are “pre-set” plays that are called from the bench. Ruiz cheats way off the plate, and the pitcher/first baseman are in on it.

We’ll focus mostly on pre-set plays here, but there are two other types of back-picks worth mentioning. Dirt ball back-picks and false-start stolen base attempt back-picks both happen on the fly without being called by the manager or catcher.

Below, I’ll walk through each type and provide a guess at whether we’ll see it more often under the new rules. While back-picks are thrown to all bases, we’ll focus on where the action is with the new rules: first base.

The dirt ball back-pick

We’ll get this one out of the way, because it is probably the most common and also the least affected by the new rules. When a pitcher throws a breaking ball that’s heading for the dirt, runners are taught to extend their lead toward second base. If the catcher isn’t able to handle the pitch cleanly, the extra momentum helps the runner advance. But, if the catcher grabs that dirt ball cleanly, the runner’s extended lead makes him vulnerable:

The “false start” back-pick

This one traces back to the moment you hear a broadcaster announce a halted stolen base attempt: “there goes [runner]…oh wait, he pulled up and stopped after a few steps.” Stolen base attempts sometimes short circuit for a variety of reasons - the runner might realize he got a bad read/jump, or he might’ve stumbled in his first few steps. Either way, stopping leaves this runner hung out to dry:

Because we expect to see more stolen base activity in 2023, we’ll probably also see more start-stop sequences. Catchers who pull up ready to throw (to either second base or first base) will be in a better position to nab these.

The pre-set back-pick

This is the type of back-pick that most resembles a pitchout. Called in from the manager (or, in some cases, the catcher), the pre-set play alerts the the first baseman that a throw is coming. The classic sign for this play is an obvious one: the catcher swipes at the dirt on the first-base side of home plate (or the third-base side, if he’s going to third base) while making eye contact with his first/third baseman.

Pre-set plays to first base are also typically called when a pitcher is trying to execute a fastball to the first-base side of home plate. Why? It’s a lot easier for a catcher to angle his body to make the throw when the pitch takes him in that direction. Below, we see Tomás Nido setting up over the outside edge and squaring his shoulders toward first base (the yellow line in the middle frame):

When Nido angles his shoulders toward first base before receiving the pitch, he’s making a tradeoff. On the plus side, he’s preparing himself for a quicker catch-and-release on this pre-set play. The cost is a called third strike that isn’t. Nido’s shoulder angle (turned away from the middle of the plate) causes the umpire to perceive this pitch as a ball. We’ll talk more about this tradeoff in next week’s post - it’s a big one.

The pre-set play is where we might see the most rules-influenced action this year. The amount of these additional throws that we’ll see will depend on how much leads grow in response to the limitations on pickoff throws and the clock. How much will leads grow? Let’s evaluate.

Back-picks target combined (primary and secondary) leads

A quick review of how a runner takes a lead. When a pitcher toes the rubber, a baserunner at first base typically sidesteps out to a 9-10 foot primary lead. This is the lead that a runner feels is safe enough to avoid a pickoff from the pitcher before the pitcher starts his delivery. After a (right-handed1) pitcher starts toward the plate, the runner (if he isn't stealing) shuffles out 10-15 feet further from the first base bag. This is the secondary lead. Combine the primary and the secondary, and you've got the distance a runner needs to travel to get back to the bag.

While primary lead sizes vary some across runners, there’s a much bigger variety in runner preferences for secondary lead size. Lead size data isn’t publicly available, but Ben Lindbergh accessed some data in 2015 via a request to MLB. Ben found that, at the extremes, Jose Ramirez (16 feet) took a secondary that was almost twice as big as Prince Fielder’s (9 feet).

Given the range of secondary lead sizes, a back-pick victim’s usual pitfall is in his secondary lead; that it was either (a) too big or (b) rushed. A rushed secondary makes it hard to change direction and get back to first base.

One effect of this year’s rule changes will likely be bigger primary leads, particularly after a pitcher has burned one or two pickoff throws. I don’t see much in the new rules, though, that would directly affect secondary lead sizes. I can see secondary lead sizes going in one of two directions.

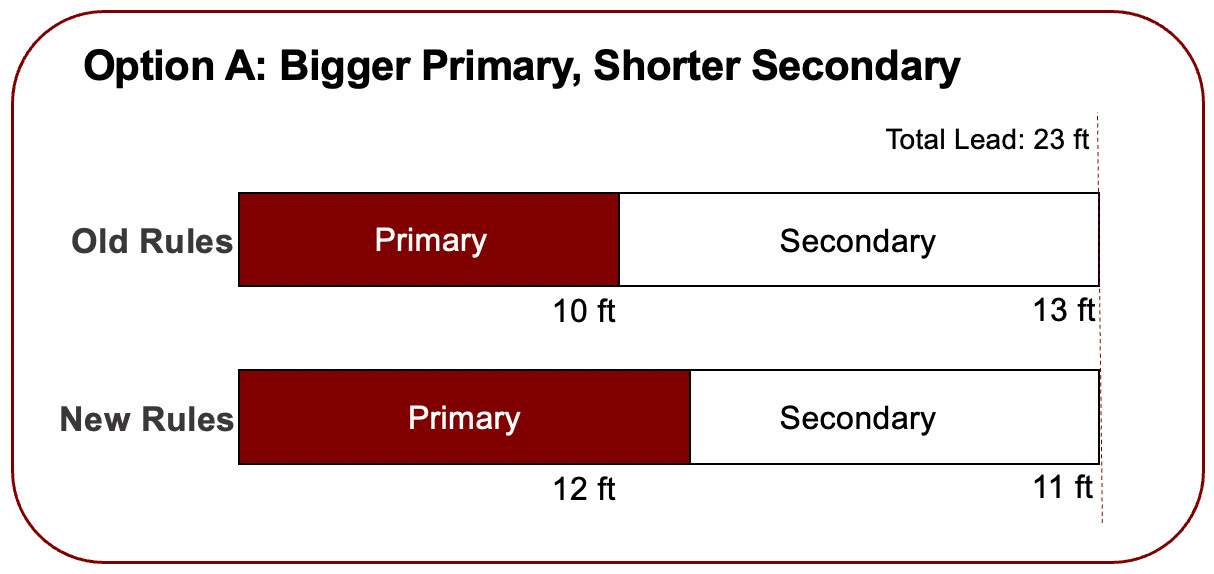

Here’s Option A, with some hypothetical lead sizes to represent a scenario in which a pitcher has burned one or two pickoff throws. In this scenario, our hypothetical runner balances out his bigger primary lead with a smaller secondary to avoid back-pick danger. The result is a combined lead that is the same (or maybe a little bigger) than it was under the old rules2.

Option B assumes the runner takes the same secondary that he is used to taking. With a bigger primary lead, the result is bigger combined lead (by 3 additional feet in this example, but the amount could be anywhere in the range of 3-10ish feet further). This additional distance (bigger primary and secondary) would really put the back-pick in play.

We’re probably likely to see a mixture of both of these options this year. Teams could speed up the learning curve by running a drill to mark off a desired combined lead distance and having runners practice Option A, but we’re more likely to see familiarity built in game action. Until that familiarity is built, we might see some runners overextend themselves (Option B).

Executing the pre-set play

Having made a case for more pre-set back-picks, we can ask a follow-up question: which catchers can execute the play well? The best indicator of comfort might be to look at who back-picked most in 20223:

Does Willson Contreras like to throw to first base? You bet he does. I would probably would too if I were as athletic as he is. Check out this ridiculous throw Contreras makes from his knees. His momentum pulls him to the ground:

If you’re looking for Statcast indicators of a catcher suited for a pre-set play, exchange time and arm strength work fairly well. Athleticism and arm strength are must-haves for any catcher who wants to try it.

But even for the quickest and strongest arms, success rates are low: across all bases in 2022, catchers caught a total of 41 runners, and Contreras only got two runners on the 29 throws he attempted to first base. He'd argue that the benefits extend beyond the number of runners he throws out:

Over the years, my [stolen base attempt] numbers have gone down because the runners know I like to throw behind them.

I wouldn’t disagree that the value of this play is primarily in what it discourages.

Are pre-set back-picks worth it, though?

Beyond a catcher’s ability, a lot of pieces need to align to get this play off. Next week, we’ll cover its many potential pitfalls and whether they’re worth the trade-offs (remember the Nido example above?). We’ll also cover catchers who might have the ability to execute this play more often, but are making a value judgment against it. J.T. Realmuto had the best pop time in baseball last year but only attempted 6 first-base back-picks - his setup might clue us in on why:

Have a great day.

Because left-handed pitchers can pick off mid-delivery, runners can’t take secondary leads against them. If you’re a pitcher, it’s a great time to be left-handed.

If a runner (who isn’t stealing) is going to take a smaller secondary to make sure he gets just as far from first base as he used to, you might ask: why take a bigger primary, then? I think it is a fair question, and one that might justify primary leads that actually aren’t that different from what they were before. It all depends on how aggressive catchers are with pre-set back-picks.

Back-pick attempts include all types (pre-set and otherwise). Thanks again to the team behind baseballR. I used their package to scrape pickoff/back-pick attempt data. I totaled back-pick outs (by base and by catcher) by cross-referencing that data against Baseball Reference’s season totals. I excluded pickoff-caught-stealing outs, but it is possible I might be off by one out here or there given the fuzzy line between how a straight back-pick and back-pick caught stealing is scored.

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EuFo!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F63512b4d-7137-4bbb-9812-c4611880303a_540x304.gif)

![[crop output image] [crop output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!GQ_b!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff001f55b-c577-48fc-9ea8-4b6c178d2881_213x160.gif)

I am also enjoying these articles. Thanks for posting them! You’re pointing out deeper strategies behind these new rules. I can’t wait to see how they play out.

Noah, I’m really enjoying these articles. Thanks so much. ⚾️