Today, I continue a series on how teams might combat the running game in 2023. If you missed last week’s post on the significance of the pickoff limit and its implications, you can find it here. You can get all upcoming posts by signing up below:

After last week’s introduction to the new pickoff rule and its expected impact on the running game, I ran across two news items that hint at one team’s effort to turn the new rules into a competitive advantage.

Here’s the first one. It comes from unidentified respondent to a recent Jayson Stark insider survey:

“The Mets are going to try a ton of stuff. I bet Buck (Showalter) is going to have his pitchers just hold the ball after they get to two (disengagements) and take a chance that they can pick guys off.”

And then this comment from an Evan Drellich tweet on Monday:

Today at Mets camp reporters were told to leave field bc of a "proprietary drill.”

Craig Calcaterra added some additional detail in his newsletter yesterday: turns out this secret drill was an infield drill.

Thanks to the Mets for providing this hook for a post speculating on potential creative pickoff plays that we might see teams experiment with in Spring Training.

NFL-i-fication of Baseball

Craig and others interpret the Mets’ secrecy around a potentially boring practice drill as yet more evidence of the “NFL-i-fication of baseball.” I agree completely that NFL-i-fication (which I’d define as transforming formerly free, open, and spontaneous gameplay into deliberate, private, and rehearsed gameplay) is happening in baseball. It was my job for a few years to help make it happen. I’ll leave judgement as to whether or not this transformation is “good” for baseball to others, though.

Whatever your stance on the broader trend, I think that in this situation Buck Showalter’s desire for secrecy is very understandable. Any new competitive advantage found under the new rules already has a limited shelf life, as other teams will start to copy it as soon as they see it used in a game.

Forward-thinking teams will have to balance the need to practice doing something new with the need to keep it away from cameras and game action as long as possible. Hiding this workout is no different from the Mets deciding to have Justin Verlander make his scheduled Spring Training start on a backfield against Mets minor leaguers instead of exposing a Phillies lineup to an extra look at him in a game that doesn’t count.

Time to speculate

How do we even know this secret infield work is pickoff-related? We don’t, but it’s probably either positioning- or running game-related. And anything positioning-related would be silly to hide. If the Mets had found a clever way around the two-to-a-side rule in the infield, other teams would be able to copy it the day after it was shown in game action. We’ve seen a lot of quotes from Mets intelligentsia on the pitch clock and on pickoff limits, so that’s where my money is. The pickoff-related ideas that I’ll lay out below also would require significant time on a practice field to build comfort before Opening Day, so we’d expect to see teams working on them as soon as possible. The Mets aren’t wasting any time here - the “secret” drill was part of the team’s first full-squad workout.

What follows is pure speculation based on my experience, conversations with those who know more than I do, and what I’d be considering in a similar position. I’ll start with a play that I think we have a good chance of seeing a few teams run, and I’ll throw in another that might be used more selectively.

Play #1: Hard Count on 4th and Short

Potential Secret Pickoff Play #1 isn’t just NFL-i-fication, it is an actual NFL play. The first play I’d like to speculate about today ties back to the “mystery insider” at the top, who thinks that the Mets will zig as others zag by leaning hard into the new pickoff limit.

You might remember that I projected teams will likely treat the two-pickoff limit as a one-pickoff limit. Doing so would avoid the potential discomfort and/or embarrassment that could come after an accidental second disengagement. Brady Williams worked under the new rule last year while managing the Durham Bulls, and he claimed (in an interview with Hannah Keyser) that he “didn't want to pick over twice and put my pitcher in harm's way.”1

So that’s one approach - the conservative one. Another way to handle a burner on first base might be to start a game of chicken. Instead of shying away from the do-or-die land that stands beyond the two-pickoff threshold, you might embrace it. You might even try to push that do-or-die pressure back on the runner himself. By showing that you’re comfortable being very uncomfortable, you might discourage runners to (literally) walk back some of the exuberance we’d expect in that do-or-die situation. When you bring the pitch clock into play, it mirrors an NFL quarterback running a “hard count” dummy play on 4th down to try to draw the defense offside.

Let’s walk through what it might look like via an example. We’ll pick a hypothetical scenario that places Trea Turner on first base and Max Scherzer on the mound. Turner is taking “I wanna run” type of leads, and Scherzer has thrown over once already. We’ll say the current count on the hitter is 1-1 (not that it really matters here).

As Scherzer gets the ball back from his catcher, Turner is getting excited about this situation. Scherzer has already burned one disengagement, so he’s not likely to throw over anymore. Turner gets a slightly bigger lead, and Scherzer (after getting his next sign) does something unexpected - he throws over to first again and doesn’t get Turner.

At this point, we’ve entered do-or-die land for Scherzer; he can’t pick off anymore unless he’s totally sure he’s going to get Turner. Turner knows this. Everyone in the park knows this. So Turner extends his lead a little further.

Scherzer is a pitcher who loves the “long hold” - prior to 2023, he’d prevent runners like Turner from stealing just by standing in a set position. The effect that long hold has on the runner is similar to the one a malfunctioning starting gun would have on a runner crouched on a race starting block.

A pitcher can’t hold the ball forever in 2023, but he can hold it for up to 19 seconds with a runner on base. Scherzer had already received his sign for the next pitch the last time he engaged with the rubber, so he can toe the rubber and come set immediately. Both Turner and the hitter can expect Scherzer to either pitch or pick off as soon as the hitter is ready (12 seconds in, at the latest) or as late as the 1-second mark.

In this scenario, Scherzer lets the clock run all the way down. Turner runs better than anyone, so this situation should have been a gimme for him. He has that big lead we’d expect him to have after two pickoffs, and because he has that big lead, he doesn’t need the best jump to steal.

But Scherzer doesn’t go to the plate - he hears a verbal signal from first-baseman Pete Alonso and picks off Turner as the pitch clock expires.

This sequence accomplishes a few goals. The two earlier pickoffs have slowed down Turner. We know from years of play-by-play data that pickoff attempts have a significant impact2 on stolen base success. The final pickoff is the one that turns Turner into a defensive lineman in a fourth down and inches situation. He may or may not know that the team on offense isn’t really going to run a play - the quarterback may just try to bait him. Turner then has to stand ready to go for the full extent of the pitch clock.

What might be more significant, though, is what the execution of this play signals. If a team were to run this play and commit to actually using the third pickoff a meaningful percentage of the time, opposing teams have to respect it. That’s where the real value is; at that point, Scherzer can use the first two pickoffs freely without having to actually use that third pickoff anymore.

Until then, the play would come with the potential downside of a gifted stolen base should Turner decide to shut it down. Isn’t that the ideal outcome, though - Turner shutting himself down? The conservative approach (limiting pickoffs to one per hitter and letting Turner do whatever he wants after that) seems like it will be a lot more costly.

Play #2: The Backdoor Timing Play

This second play is a little more out of the box and is probably best demonstrated by a real, but reversed, example from across the diamond.

The date is June 30th, 2021, and pitcher Chris Bassitt is dealing with runners on first and third. Isiah Kiner-Falefa is the runner on third, and he’s dancing around the bag. Bassitt has not yet attempted a pickoff at third base.

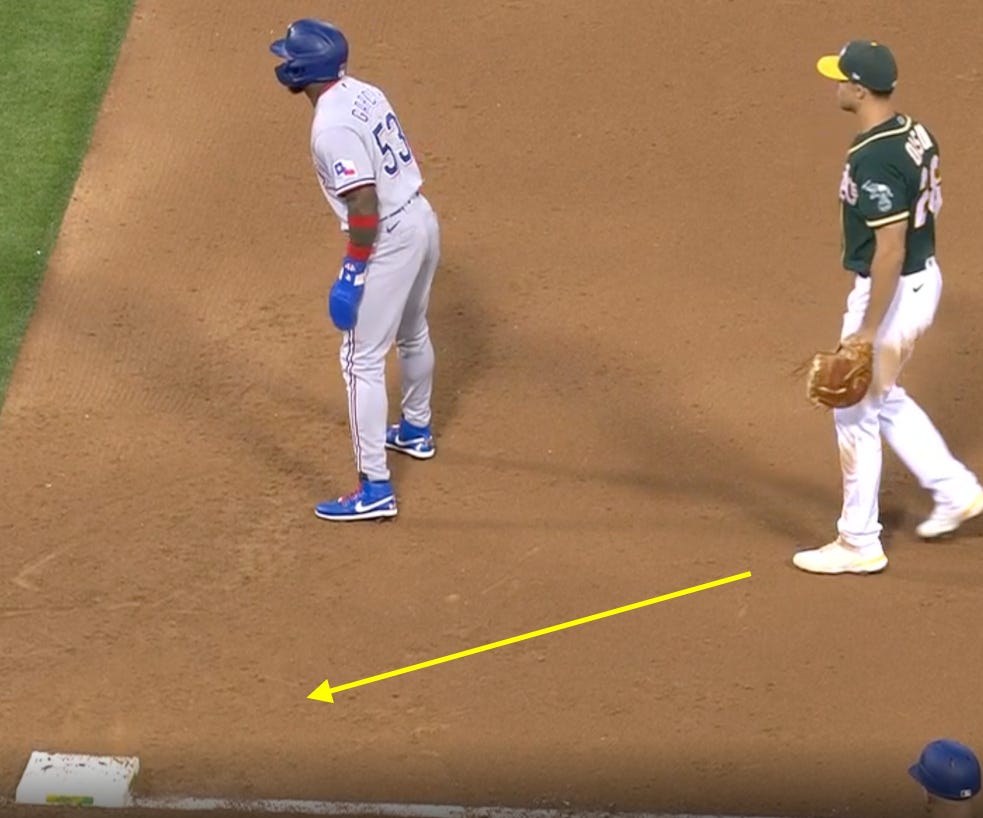

One of the reasons pitchers hardly ever throw over to third (other than the juice not being worth the squeeze) is that the third baseman is not standing ready to receive a pickoff throw like a first baseman would be. Bassitt’s third baseman, with a left-handed hitter at the plate, has been playing as far off the bag as he can without completely disregarding Kiner-Falefa:

After watching Kiner-Falefa’s act for six pitches, Bassitt has had enough of it. We see Bassitt step away from the mound, look to third base while picking at the air around his shirt (middle frame), and then hold a stare over in that direction for another moment. After the final pause in that last frame, he moves back to the rubber to get set:

I read this as a sign. Maybe not as a rehearsed play, but an attempt to create one on the fly. It tells the third baseman to wait until Bassitt comes set and then break toward the bag to receive a throw that Kiner-Falefa won’t be expecting:

That’s what happens, and they almost catch Kiner-Falefa flat-footed:

After the throw, we see coach Tony Beasley break it down. He points at the third baseman: “see, he came from over there.”

Now imagine the same play flipped around to first base. How would it look? Similar, but different. It might start kind of like the image below - the first baseman playing off the bag, but not way off3. Bassitt and Olson would’ve communicated on a timing method (say, one second after Bassitt comes set) and a signal to put the play on (say, Bassitt picking at his shirt). Once the sequence starts, Olson breaks toward the bag:

Bassitt spins and hits Olson with a throw in the chest (because, as would be the case for an NFL receiver, it’s harder to catch something thrown at your feet while you’re moving).

Why do this one?

This play would be used to free up the first baseman. It’s a twist on a similar play that we don’t see nowadays, but was used in the past as a way to catch a trailing runner (in a 1st/2nd scenario). Olson can play off the bag, which gives him more range and depth as an infielder (all the more important given there won’t be an extra infielder playing behind him). If pitchers are going to ration pickoffs like we think they might, does it make sense for a first baseman to take this stance on every pitch?

Maybe it still does. But if a team can execute this timing play, he wouldn’t always have to. Because the first baseman cuts behind the runner, the play would force runners to rely on their first-base coach to get them back to the bag. After running it successfully a few times, the pitching team could even deke the play by having the first baseman crash (causing the first-base coach to yell “BACK”) while the pitcher throws a pitch instead of a pickoff.

Easy to talk about, harder to execute

I don’t want to oversell this one. The Bassitt example above featured a right-handed pitcher throwing to third base. Because he can look at the base the whole time his teammate is breaking toward it, he can make a better throw to a target that didn’t exist seconds before. At first base, this is only true for left-handed pitchers. Right-handed pitchers have to make a blind throw to a moving target, which can spell disaster if poorly timed or executed. In fact, there’s only one left-handed pitcher who’s tried it in the past two seasons:

Madison Bumgarner, with ice in his veins. In this case, the third baseman cheated a bit toward the bag. There’s a slight look from Bumgarner beforehand that might’ve set it up, but the camera angle makes it hard to say. Regardless, the takeaway might be that the “backdoor” timing play at first base might only be workable for left-handed pitchers.

This play also requires an agile first baseman. The act of breaking toward the bag, receiving a throw, and making a tag is middle-infielder-like. For some (Rowdy Tellez, Josh Naylor, maybe Vladimir Guerrero Jr.) it will be out of the question. For someone like Rhys Hoskins or Matt Olson, this play might be more feasible. It would require tons of reps to get right, so if the Mets are working with Pete Alonso on something like it, they might need to close off the rest of camp to reporters.

We’ll have to wait and see

Drellich seemed to think that kicking out the reporters on Monday was a bit harsh and “counterproductive” in an entertainment business. I disagree with that take; these new rules and the creative approaches taken to adapt to them should enhance the entertainment value of the game. I don’t feel like I’m missing out if I don’t get a beat story that attempts to describe what happened in camp on Monday. I’m fine waiting to see whatever it was in the context of a Spring game (or one that matters) soon enough.

This series will continue with a look at how catchers will play a role in curbing the running game in 2023. I’ll also cover the implications of a significant recent development (pitchers calling their own games via PitchCom) in a post next week. Until then, have a great week and enjoy the start of game action on Friday.

The Rays are calling up Williams as third-base coach on big league staff in 2023. The Rays are known for promoting from within to fill major league coaching jobs, but this move seems especially savvy given Williams’ familiarity with the new set of rules. The move makes you wonder how much perspective other clubs have tapped in their own minor league coaching staffs.

If you didn’t catch the series intro, Russell Carleton found that pickoffs lower stolen base success rates by 12 percentage points.

With a left-handed hitter at the plate, Olson would likely be playing this close to the line even if he didn’t have a runner to worry about. With a right-handed hitter up, he might normally be closer to second base with no runner on, but to press any kind of viable pickoff threat, he’d have to stop right about there.

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KLzp!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1a4284a5-9a05-4704-a40a-758b764aeccf_540x304.gif)

High school teams have been running these plays and defending them for decades, albeit without a pitch clock. It is not rocket science.