Today, a few takes on:

Paul Skenes’ evolving pitch mix and where it could be heading

The “fine target” strategy that might be spreading across the Yankee rotation

1. Skenes’ splinker

A lot of ink has been spilled on Paul Skenes’ Friday outing, and deservedly so. Skenes punched out 11 Cubs hitters and didn’t give up a hit. I won’t do a full recap here, but I wanted to touch on one aspect of Skenes’ outing that stood out to me: he did it using a pitch that he doesn’t even have a full year of experience throwing. What’s the new pitch going to do for Skenes?

To back up, here is Skenes’ pitch mix when he was drafted by the Pirates:

Fastball (96-101 mph with kind of a flat/running profile; lacks “jump”)

Changeup (86-90 mph with plus sink/fade)

Slider/Sweeper (82-88 mph with varying shapes; some harder/shorter, some softer/wider)

Curveball (80-84 mph; a bigger, vertical shape that he can land for a strikes)

This mix is already a lot to work with. Against college hitters, Skenes didn’t really need anything but a fastball/slider combo. But when he began to plan for facing professional hitters, Skenes thought he needed something more (per Sam Dykstra/MLB.com):

As his four-seam velocity increased, college hitters were having difficulty catching up, and the right-hander didn’t want to give them a slower fastball they could touch. But with pro hitters (and their improved bat speed) looming after the Draft, the righty got to work after the College World Series on incorporating a fastball that would have more arm-side movement.

So Skenes wanted something that was a few ticks off his 100 mph fastball to get early-count contact outs. What he ended up with wasn’t quite that, though: enter the splinker (or the splitter/sinker). Skenes first threw it by accident, apparently - his finger slipped off the baseball as he was throwing a fastball.

When Skenes’ finger slips off in just the right way, the pitch is too nasty to be classified in the “pitch to contact” category:

The splinker has become Skenes’ second pitch. In his 100 pitches thrown last Friday, Skenes threw almost as many splinkers (33) as fastballs (41). At 93-96 mph, it sits right in the middle of Skenes’ fastball and changeup.

Skenes only threw his changeup four times on Friday, but it also looked pretty damn good:

To me, Skenes on Friday was a pitcher in transition. His pairing of a generational arm with the physical aptitude to manipulate the baseball has given him too many options; his pitch mix will become a topic that we debate. Take that changeup, for example; it serves a similar purpose to the splinker. At 85 mph, it’s even harder to sit back on than the splinker is for a hitter geared up for 100 mph. But the splinker has a ton of depth for a pitch in the mid-90’s. Hmm…

I could see Skenes’ repertoire going in a few different directions, including:

1) Primarily fastball/splinker with the occasional breaking ball; changeup shelved (similar to what he showed on Friday)

2) Splinker takes place of primary fastball; 4-seam fastball shelved/used occasionally; changeup featured as “slower fastball”

Option #2 would be pretty unconventional. It might be the quickest way to get fired if you’re Skenes’ pitching coach.

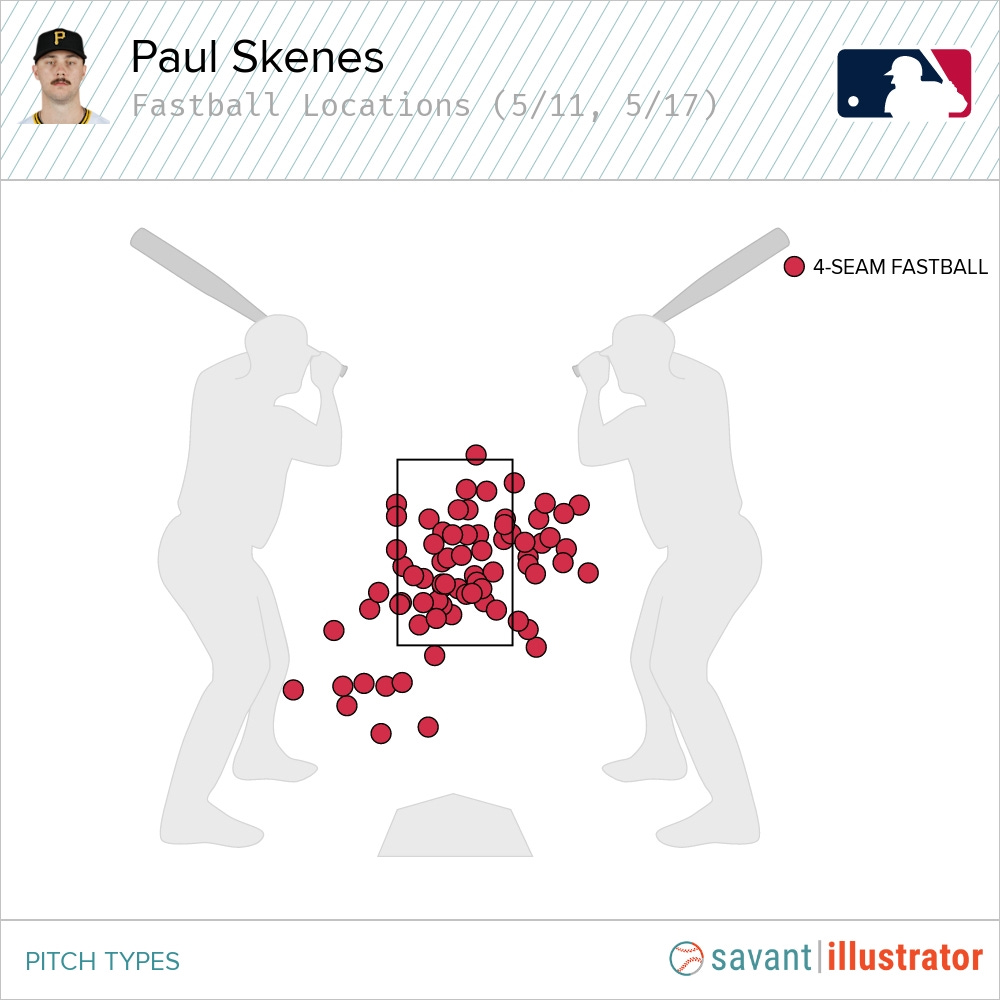

But if Skenes has an Achilles’ heel, it’s probably his fastball command. Skenes’ catchers use the down-the-middle target approach, so there’s no need to chart targets. But with that middle-middle target, here’s where Skenes has ended up:

That’s a pretty wide spread. If a hitter wants to sit on a Skenes fastball, Skenes can’t be sure that he won’t serve one up in a hittable area. And this type of approach (setting up middle and letting the ball go wherever it does) has an effect on umpires: you get fewer borderline calls.

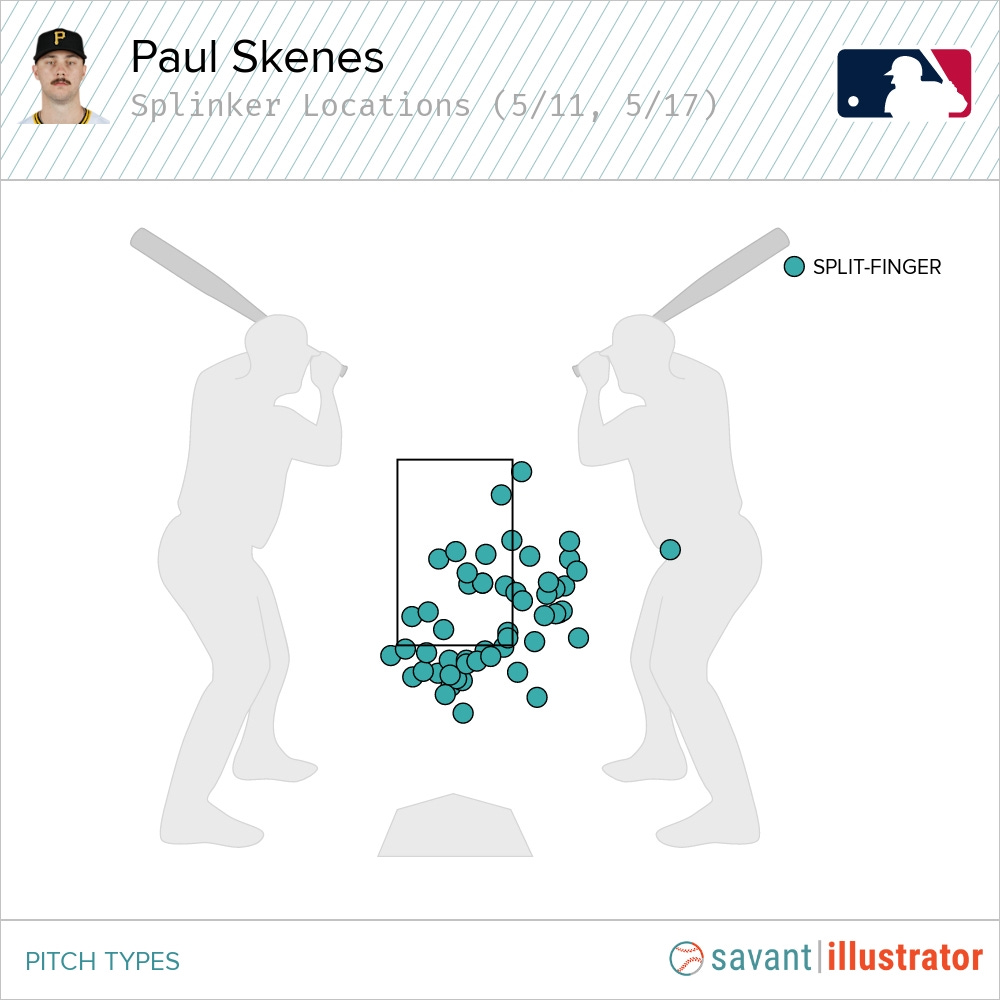

On the other hand, here’s where he’s landed his splinker:

It might look worse than the fastball, but the pitch moves a ton; so the pitches down and to Skenes’ arm side are both (a) safe from danger and (b) likely to get hitters to chase. For how new this pitch is for him, he’s executed it pretty consistently.

These days, pitchers focus a lot on their ability to manipulate pitch shapes. Skenes is clearly really good at that. He apparently tweaks the shape of his slider depending on how “big” he needs it to be. He’s done it with the splinker, too. And with the splinker, he’s found a pitch that he can throw for strikes. It may not be a conventional fastball, but there’s no reason it can’t take the place of one.

2. Stanton update

Two weeks ago, I wrote about some troubling developments for Giancarlo Stanton at the plate. I pointed out two concerns that led to that conclusion:

Plate discipline: Stanton seemed to be a few ticks late in tracking chase breaking balls.

A long swing: Stanton’s bat has been a few ticks slow to get into the hitting zone

Some kind friends have pointed out that Stanton’s offensive production has turned around in the days since that post. In 8 games, he’s hit 4 earth-shaking home runs and 2 doubles, while striking out less often (26% over that stretch).

That said, I still wouldn’t change my conclusion from a few weeks ago. I think we’re seeing a change in the quality of the pitches Stanton is seeing.

The locations of Stanton’s extra-base hits in May:

These are mistake pitches that a hitter gets some extra time to pick up - hanging breaking balls or fastballs that missed the target. Not much need to shorten up his swing, either: all but one of these was in the 78-92 mph range. As we’ve recently learned, Stanton swings harder than any other big leaguer. So mistake pitches to him are more costly than they are to other hitters.

Here are two points that teams facing Stanton could consider:

On the first pitch: Stanton has taken 65% of fastballs in the strike zone (higher than 78% of big league hitters with as many or more at-bats)

When the pitcher gets ahead: Stanton has chased 41% of breaking balls outside the zone (higher than 73% of big league hitters in the same group)

It would seem like you could follow this plan to get Stanton out. The Rays, with exceptions here and there, tend to follow this plan to get most hitters out.

But pitches like this 0-1 heater from Brad Keller:

…and this 1-2 curveball from Spencer Arrighetti:

…are head scratchers. The Keller fastball missed its target across the plate - but even if it hadn’t, a 92 mph fastball over the plate to Stanton is a favor in an 0-1 count. And Arrighetti might’ve been trying to freeze Stanton with the 2-strike curveball above, but why risk making a mistake with three chances to get Stanton to fish out of the zone?

I don’t like the idea of betting against Stanton (or any other player). Major league baseball players are also people, and they’re all incredibly talented. It seems unlikely, though, that the quality of pitching he’ll see the rest of the year will look like what he’s seen over the past two weeks. The path to get him out is clear for any pitcher who can execute. I probably didn’t appreciate an aspect of Stanton’s game enough, though: executing pitches against an intimidating figure like him is much easier said than done.

3. Strike calls for Yankee pitchers

Baseball Prospectus ran the post I wrote on Marcus Stroman’s approach to setting catcher targets last week. It was interesting to run the “pitcher-generated bonus strike calls” through their model (mine was done using Baseball Savant’s).

On their leaderboard, Stroman still comes out way ahead of every other pitcher. But the entire Yankee rotation was in the top 10: after Stroman, Carlos Rodón came in 2nd (in a near-tie with Luis Castillo). Nestor Cortes wasn’t too far behind Rodón.

Usually, a one-team leaderboard for a model like this one suggests that there is some other source of variation (like the catcher) that might deserve more credit than it is getting (or that there’s some tracking glitch in Yankee stadium). Austin Wells and Jose Trevino have been splitting time roughly evenly, and both have graded out well in their contributions to picking up more strike calls.

It’s also possible that Yankee catchers are experimenting with more targets like the extreme ones Stroman has been asking for. If the rotation is using aggressive targets and the bullpen isn’t, the target strategy might also explain this leaderboard a bit. I haven’t watched enough Yankee games to evaluate, but the bits I have seen definitely point to more of a “fine target” team strategy than I’d seen in April.

Here’s a Rodón fastball target from two weeks ago:

You’re not getting this strike call if your catcher doesn’t set up with his body over that inside edge: Jose Trevino is really good at combining an aggressive body position with a “glove drop”. The combined effect is to move the umpire’s viewing lane so far that he can barely see anything at all:

The Yankees and Rays share a division and seem to be taking very different approaches to setting targets for pitchers. There’s the Stroman approach and then there’s the no-target approach. A team’s approach to setting targets really does impact the way pitchers work and the way at-bats play out. It’s also very hard to quantify which team has it right.

4. Back-picks are down…

Leo Morgenstern had a piece at FanGraphs last week on catcher back-picks (post-pitch catcher pickoffs). When I did a deep dive on the back-pick here last March, I wondered if teams might try to use them more aggressively to control the running game in a pickoff-limited environment. I didn’t think there was a strong case to do so: the play comes with a low success rate and other costs (umpires are less likely to give you a strike call, for example).

Leo ran the numbers: last year, back-picks were down slightly. And this year, we’re on track for another decline in back-pick use. The verdict is in: teams don’t think back-picks are worth it. Makes sense.

5. …but the timing play is coming

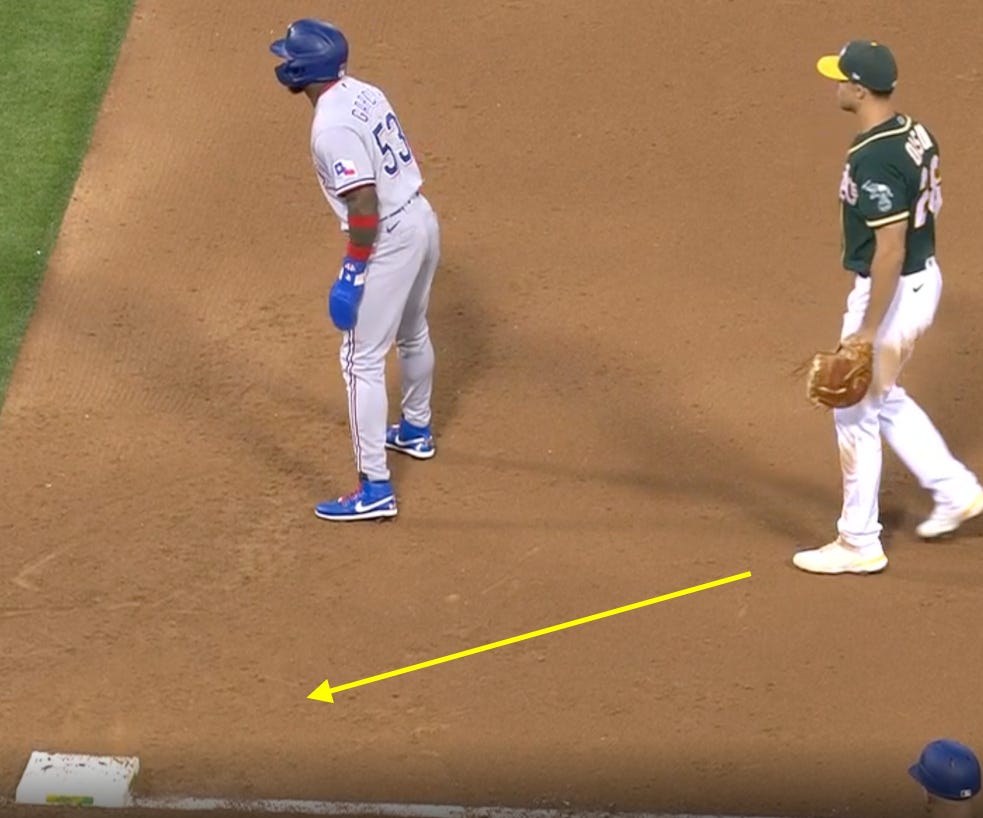

One reason to shy away from the back-pick is the potential for disaster; it can be hard for an infielder and catcher to be on the same page, and if they aren’t, the back-pick throw can sail into the outfield. The communication dynamic is changing, though. Consider this play:

With PitchCom (the device pitchers and catchers use to call pitches to each other), plays like this one become possible. In addition to the pitcher and catcher, infielders are also allowed to wear an earpiece. And you can use a PitchCom device to call for more than pitch types - you can also call for a pickoff.

Watch the third baseman (Ryan McMahon) closely here. With a left-handed hitter up, he starts in the 5/6 hole; his positioning is about as aggressive as it can be to try to play to a typical left-handed spray chart. But he’s a long way from the third base bag.

McMahon breaks for third super early (as the hitter is swinging and missing). If the hitter had connected, McMahon actually would’ve been caught in motion:

McMahon’s early break is part of a designed play. If this weren’t pre-set (most back-picks and pickoffs aren’t), McMahon could only break once he saw his catcher pop up to throw. An on-the-fly back-pick here wouldn’t have worked, though. The runner would’ve had too much time to get back and McMahon would’ve had too much ground to cover.

For teams that can get organized around it, PitchCom offers this potential. The concept above doesn’t have to be constrained to back-picks. You might remember me speculating on the Mets’ use of a backdoor timing play last year. Using a PitchCom device, either the first or third baseman can play off the bag and surprise a runner like McMahon did.

I haven’t seen this play at first base yet, but it would look something like this:

We do know that at least one team is working on something like it:

[Diamondbacks’ Bench Coach Jeff] Banister said the Diamondbacks will use a PitchCom command for a timing pick, as opposed to a straight pick. A secondary command then will come from a body motion by the catcher or third baseman, who has a direct visual to the runner on first base. The pitcher picks up the motion, then fires quickly to first.

A play like this one could’ve been installed at any point last year. But I think it’s taking a spike in stolen bases (and first and third running plays) to force defenses to consider such a coordinated and complex play. The tool is there to make it happen. We’ll see which team is first to practice and use it.

Have a great week!

Killer stuff as always, Noah.

Any reading you'd recommend (besides your own!) on catcher targets (no target vs. fine target, etc.)?