1. Sound the alarm on Stanton?

This swing caught my attention on Sunday: It’s an 0-0 changeup from Tarik Skubal to Giancarlo Stanton.

Here, Stanton is late - on a changeup.

Now, there are ways to explain this swing that don’t fault Stanton. The weather, for one. This is a rainy getaway day game that didn’t make it the full nine. Skubal also had a great changeup working on Sunday. He got whiffs up and down the Yankee lineup with it.

It could also be possible that Stanton was looking for something soft and was caught in between. But sitting on Skubal’s changeup on the first pitch wouldn’t make a ton of sense - Skubal’s changeup moves away from the zone when it’s working (like it did here) and not to a good hitting location.

But after watching recent at-bats, I think Stanton was just really late - which is a recent pattern for him. At the plate, he looks like he’s aged two years in two weeks.

Here’s a swing from the day before:

Another first pitch, but a fastball this time (97 mph from Casey Mize). And Stanton is super late. This is like an emergency two-strike swing.

And then there was this one from last Tuesday:

A nasty 2-strike sweeper from Jacob Webb. Let’s break it down frame by frame:

Frame 1 (left, below): It looks like a strike for the first 15 feet or so.

Frame 2 (right, below): No longer a strike. Disciplined hitters are stopping here.

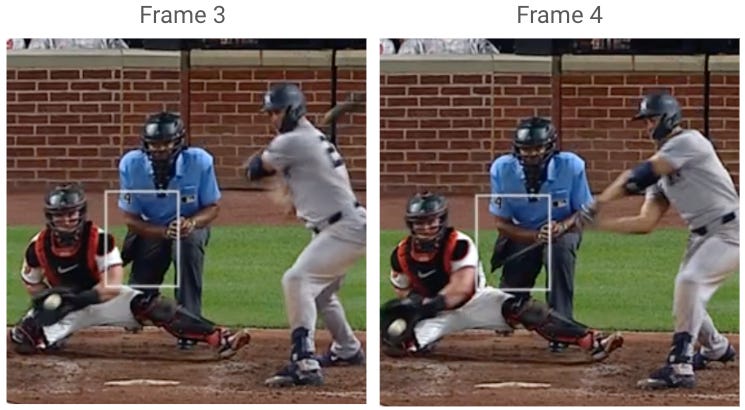

These next two frames expose two separate (but related) issues:

Frame 3: Stanton’s decision-making. He’s making his decision to start sending his hands toward the plate when the pitch has crossed into the other batter’s box.

Frame 4: Stanton’s slow bat. The gap between pitch and bat in this frame has turned the sequence into a viral one. Less noticeable is that even if the pitch were hittable, Stanton would still be too late to get his bat through the zone.

So Stanton is both (a) not tracking pitches well and (b) really long with his swing. Not a good combination.

Stanton’s line over the last two weeks: 53 PA, 21 K, 4 BB, 11 H, 2 HR1. A saber-minded analyst would say that two weeks can’t tell you anything about a hitter. But the advance scout would say otherwise. When we dive into the video, we get into this one of those advance scout-y debates: what do we do with information that we can’t quite quantify on Stanton’s swing, like how late he is and how slow his bat is right now?

I’m ready to be proved wrong, but I’d be worried.

2. Whiff-heavy games

I put this table together when I was digging in on Stanton:

It’s an arbitrary stat, one that counts how many games in which a hitter swung and missed at least 5 times. If anything, this tells you that counting whiffs at this point in the year won’t get you too far in assessing early performances. That’s in part because all whiffs aren’t created equally.

The quality of the pitch matters. There are a few teammates on here (Harris II-Kelenic, Siri-Arozarena-Ramirez, Harper-Castellanos, Judge-Stanton) who may have faced stretches of tough pitching.

Situational factors and hitter intent also matter. Bryce Harper is not struggling like Stanton is. But they’ve swung and missed at roughly the same rate (15%2).

Harper’s whiffs don’t look like Stanton’s whiffs, though. Here’s one:

This is just Harper guessing he’d get a 3-1 heater and getting fooled. If he did get a fastball on this slider’s initial trajectory (down and in), Harper would’ve clobbered it.

Ideally, we’d develop a “whiff quality” metric that would match what we see when we look at Stanton’s whiffs next to Harper’s. Publicly available Statcast data gives us some of the important information we need to develop such a metric (pitch location and context). But to get the full picture, we’d need to fold in data on the path of the bat3. That’s the next frontier.

3. It’s a slow burn

On Friday, I broke down the recent spike in stolen base activity we’re seeing and the unlikely contributors to that spike (slower runners).

This weekend, more of the same. From Friday’s games through Monday’s games, we saw 91 stolen bases. Over a full season, the weekend’s pace would top 4,000 stolen bases. The success rate on stolen base attempts was up, too (83%).

Here are some runners who stole a base last weekend (last year’s season stolen base total in parenthesis):

Jake Bauers (3)

William Contreras (6)

Willson Contreras (6)

Aaron Judge (3)

Nathaniel Lowe (1)

Christopher Morel (6)

Zach Neto (5)

Patrick Wisdom (4)

Nobody on this list falls into the “Burner” category from last Friday’s breakdown - they are all in the middle of the pack in terms of raw speed.

Where are all of these guys finding opportunities to run? See Takes #4 and #5 below.

4. Pitchers checking out

We’re reaching a breaking point here. Sal Fasano (coach and former catcher), speaking on behalf of the big league catcher bloc:

“We behind the plate are at the mercy of the pitcher”

J.T. Realmuto, quoted in that same Ken Rosenthal/Trent Rosecans article, agrees:

“As the years go, it’s going to be where you don’t have a choice…Either you can hold runners or you can’t pitch.”

A subset of pitchers (some, but not all) are forcing catchers play with both hands tied behind their backs.

Fasano and Realmuto are referring to stuff like this:

This is a tie ballgame in extra innings. Edwin Díaz never checks the runner at 2nd. He then takes 1.62 seconds to deliver this pitch. A catcher here would need superhuman arm strength to throw out Christopher Morel (who has average speed, by the way). This was a huge play: it bumped up the Cubs’ chance of winning the game from 39% to 51%.

Here’s another one (from a few weeks ago). Pirates-Mets. Tied at 3 in the 8th inning. Aroldis Chapman has runners on 1st and 2nd. Chapman is upset and distracted by a ball/strike call made earlier in the inning. Does he look like he forgot he had a runner to check on?

I clock this delivery at 1.98 seconds: and an easy double steal to set the Pirates up for a two-run lead on the next swing.

I’ve written about some of the things pitchers can do to slow the running game within the new set of rules. The most impactful tactic, though, would be to develop quicker deliveries.

A 1.6 second delivery with a runner on base won’t fly anymore. Just ask Corbin Burnes, J.P. Sears, and Logan Webb - together, they’ve allowed 27 stolen bases this year.

5. The 1st-and-3rd play

Here’s the William Contreras stolen base from last weekend:

Defensively, teams don’t really risk the throw down to 2nd anymore. They may bluff to 2nd and check 3rd (like Arizona did on the Contreras attempt above), but they don’t want to risk actually throwing the ball down to 2nd.

Offensively, we’re now seeing that it doesn’t really matter who you send from 1st on this play. Matt Chapman, Joey Gallo, and Rhys Hoskins have all done it this year. The rate of success on this play (when you consider “success” as a steal of 2nd or of home4) is up quite a bit:

The proportion of 1st-and-3rd stolen bases relative to stolen bases across other situations actually isn’t trending upward. But because teams are running more across the board, that still means nearly twice as many 1st-and-3rd stolen bases than in the pre-rules era. We’re finding out that some of those are going to slower runners.

Defensively, what is the response to this? Sam Miller has already covered this in detail, but maybe it’s time to consider some wackier options.

Here’s one that gets its inspiration from this play:

Check out second baseman Jared Triolo! He originally moves to take the throw at 2nd, but he sees the runner breaking and starts to cut down the distance to home plate before firing home.

Triolo moves so quickly that the sequence almost looked like the “cutoff play” you’d see run in a high school.

The cutoff play is a little different than the one above, though. In the cutoff play:

the shortstop (Oneil Cruz in this case) would break to 2nd to take the catcher’s throw

meanwhile, the second baseman (Triolo) would move into a cutoff position near where Triolo ended up.

If the second baseman sees the runner at 3rd break, he cuts the throw off and redirects home. If the runner at 3rd stays put, the second baseman lets the catcher’s throw come through to the shortstop covering.

Big league teams don’t run this play and probably shouldn’t. It’s costly to vacate the middle of the infield and send both the second baseman and shortstop to cover a throw.

But there is a much riskier and more dangerous alternative to the second baseman’s cutoff play, and it also comes from the world of high school baseball: you could have the catcher throw the ball right back to the pitcher5. Not as an optional cutoff, though - that would probably be too crazy.

Run this one a few times and offenses would have to hold the runner at 3rd. And if the runner at 3rd can’t break on a throw up the middle of the field, catchers can go back to throwing down to 2nd a little more often.

Have a great Wednesday!

That line includes a home run last night on a first-pitch Justin Verlander slider that hung over the middle of the plate. To me, Stanton’s swing looked like a fastball swing leaking into that hung slider…

per Fangraphs

MLB’s new tracking technology (Hawkeye) does track bat locations, but the data isn’t publicly available.

If you consider “success” as also including plays in which the runner at 2nd is caught stealing but the runner at 3rd scores, the success rate is even higher.

You’d need a pitcher with a particular delivery to do this - not one who falls off the mound significantly to one direction. It could also be incredibly distracting to a pitcher to think about receiving a throw after every pitch during an at-bat, so probably not gonna happen.

I’m new to your newsletter. It’s fantastic. I know how hard it is to put these together so I appreciate the context, content and effort. Thank you.

One of the reasons, among many, that I like your articles is that you highlight areas one might not think about. I am certain the Yankees are jumping for joy that they have Stanton signed through 2027 at 30M a year.