Welcome back! To close out my broader Spring Training series on the 2023 running game, I’m going to splash some cold water on the idea that back-picks are the perfect counter to the rules-related advantages handed to runners this year. If you missed the first post on back-picks, here’s the link.

If you just want a quick recap:

Across Spring Training camps, catcher back-picks (throws behind runners) have been a hot topic.

The logic: runners might feel encouraged to take bigger leads in 2023. Back-picks are (unlike pickoff throws) an uncapped mechanism to catch runners whose secondary lead pushes them too far away from safety.

Back-picks look cool and discourage baserunners, even if they don’t erase them that often.

So why don’t I think back-picks are the solution? I’ll start with the obvious: they aren’t always executed.

Misplays can sting a defense

A back-pick looks slick when everything goes right. But when the catcher and first baseman don’t connect, this happens:

That runner is Alejandro Kirk1, and Rutschman’s errant throw turned him into track star.

There are at least a handful of plays like this one among the few hundred back-pick throws made last year. A back-pick error sends the runner to second (or third), which is costly for the defense. Over the course of a season, runs saved by back-pick outs are partially negated by the runs allowed by back-pick errors. And you might remember that there weren’t many back-pick outs to begin with in 2022.

Are there bigger things to worry about?

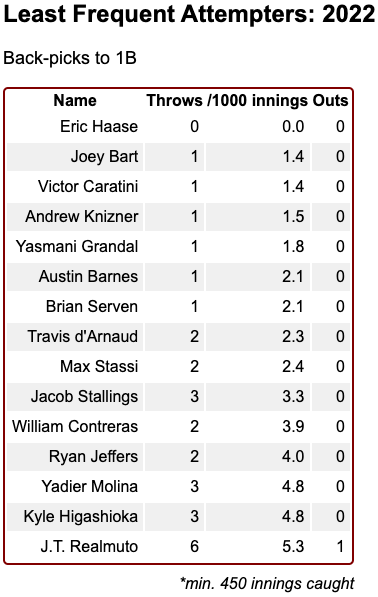

In Part 1, I spent some time highlighting how difficult it is to execute a back-pick play. I suggested that athleticism is a trait shared by those who do it often. I didn’t include the list of catchers who rarely tried it, though. Here that is:

I think relative2 athleticism explains part of this list: Grandal has dealt with back and knee issues; Caratini, Knizer, Stassi, and Molina all ranked among the weakest pop times in baseball last year.

But there are some others on this list that can’t be explained by a relative lack of athleticism. J.T. Realmuto? A super-athlete. Travis d’Arnaud posted a sub-2.00 average pop time last year. Barnes and the younger Contreras are athletic enough to play multiple positions.

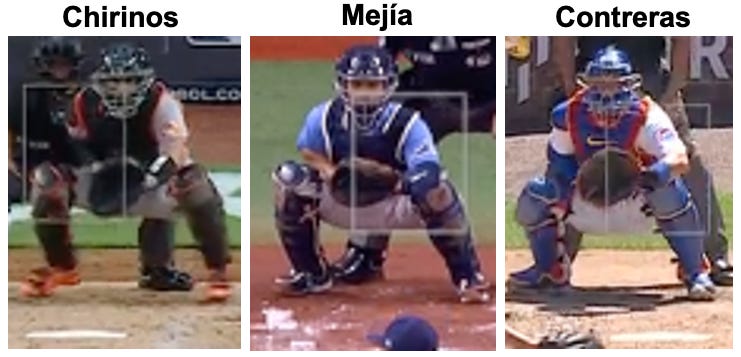

So what is it that separates this group? Check out how they set up:

It’s the knee. The knee-down technique, while initially slow to catch on at the big league level, has spread like any other run-saving strategy that doesn’t cost clubs any money. The approach isn’t anything brand new, but it wasn’t always something catchers would attempt to do with a runner on base or with two strikes. Tyler Flowers was one of the first to embrace it in every situation (runner on or not). The additional called strikes Flowers picked up made him one of the most valuable players in baseball at one point.

The knee-down becomes the norm

Knee-down skeptics initially had a lot of questions, like “how do you throw from that position?” Well, you don’t, really - or not as well as you otherwise could. This technique accepts a tradeoff. For thousands of chances to increase the chance of getting a called strike, these catchers will pass up a few dozen chances to throw out a runner.

The tradeoff has been well worth it from a numbers perspective. But it has taken years to wash away the stigma against the way the knee-down looks before it could spread across the league.

How it works: The knee-down position creates an angle for umpires that makes pitches appear higher than they really cross the plate. Tanner Swanson, the former catching coordinator for the Twins, implemented it across their minor league system while Ryan Jeffers was a young prospect. Swanson tested the limits of how far you can take it: he even experimented with having minor league catchers set up with both knees down. The double-knee was a little too wacky to make it to the big league level, but you can picture what it might’ve looked like. It was kind of like this position, but even weirder - the right leg would be tucked behind the catcher.

After the league took notice of Swanson’s work, other clubs sought him out - he took a major league job with the Yankees in 2019, and he’s already helped Jose Trevino and Kyle Higashioka vault to the top of framing leaderboards. The knee-down approach is now the norm at every level. It has spread across the big leagues and all the way down to the college level.

Back-picks and framing don’t mix

The list and screenshots above prove something: with a few exceptions, catchers who didn’t back-pick often in 2022 were knee-downers. And we’ve established a connection between the knee-down and framing. So, what if we compare the framing value added by each catcher to his back-pick frequency? We get:

The upper-left includes the group we just covered. This group made a sensible tradeoff for 2022. If runners don’t go crazy in 2023, that tradeoff will remain sensible. But if leads get bigger and runners feel more comfortable wandering, the knee-down limitation might become a potential issue.

The group in the bottom right loves to back-pick. It also happens to include some of the league’s only remaining knee-down holdouts:

These positions are not great positions to get called strikes on low pitches. Check out Chirinos on the left: his mask is as high as the umpire’s.

Do any catchers get the best of both worlds? A few. The group in the upper-right includes catchers that both receive well and throw behind runners. The aforementioned Swanson was ahead of the curve once again in 2022 in making the knee-down position one Trevino could throw from. This one is particularly impressive:

Trevino receives a pitch on the opposite side of the plate from where he set up, pops his right knee up as he’s receiving the pitch, and then pivots to make a great throw.

As we gauge the approaches catchers are taking in 2023 to adjust to supercharged base running, we should watch Trevino and Swanson closely.

A back-pick is basically a pitchout

Trevino gets a lot of calls other catchers don’t get. But on the pitches he tries to back-pick on, even he has trouble picking up the strike call. That throw above was a great one, but Trevino didn’t get a chance to present the pitch to the umpire before making it. The result is a ball on a pitch that was well inside the strike zone. If Trevino hadn’t gotten the third out, the count on the hitter would’ve been pushed to 3-1 instead of 2-2. For the average major league hitter, that’s a swing from a 1.027 OPS (Aaron Judge) to a .569 OPS (Myles Straw).

It turns out that, even for catchers who don’t “set up” for the back-pick with two knees angled to first base, the act of loading, pivoting, and firing to first base interrupts an umpire’s chance to see where the pitch crosses the plate:

When catchers consider upping their back-pick game in 2023, they might keep this in mind. Not only do you lose calls by adopting a back-pick friendly approach, you also lose a lot more calls on the pitches you throw on.

Contreras watch

The running-game-to-pitch-receiving tradeoff that teams will be forced to reconsider in 2023 can be personified in two brothers. Willson Contreras doesn’t pick up more called strikes than the average catcher, but he seems to be a firm believer in the value of his aggressive play behind runners at first base.

William Contreras shares 50% of Willson’s DNA, so his place on the “fewest back-pick attempts in 2023 list” probably can’t be explained by a lack of athleticism. William came up with a different team and became a knee-downer:

Willson has spent his entire career with one organization. Now, wearing Cardinal red (that screenshot is from last week), he continues to zig as the rest of the league zags. For him, it’s not about how many runners he throws out, how many throws skip into right field, or how many calls he misses while he bounces around back there. He believes in the back-pick as a deterrent.

William might believe that too - he’s just going about it in a different way:

Have a great week.

Some Alejandro Kirk stats: 0 career stolen bases; 0 career attempts; slower top speed than all but a dozen major league players.

I say “relative” because these are all professional athletes who are faster, more flexible, and stronger than the rest of us.

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iaup!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff5340adf-b995-4c8a-a655-8f31a7f80dec_540x304.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!10QO!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F29bd9d29-c369-42d7-bfeb-50c981e831ee_540x304.gif)