Targets matter

A catcher's setup is more than just a formality

3-0 is the most boring count in baseball. When the count hits 3-0, pitchers throw fastballs (91% of the time, in 2022) and hitters don’t swing. Sure, the occasional hitter ambushes. But 88% of the time1, the hitter moves into auto-take mode and turns into a spectator. We’re all watching to see if the pitcher throws a fastball in the strike zone.

Here are few catchers setting up to receive a 3-0 fastball:

These targets are boring. The first one is up/middle, the second one is down/middle, and the third one is middle-in (all to right-handed hitters). These targets are pretty demonstrative of how catchers set up 3-0.

Let’s add a fourth catcher to this collage:

Whoa. Who’s that catcher on the far right? He’s setting up off the plate, almost on the white line of the left-handed batter’s box. This is a target that begs for a fastball to be thrown outside the zone.

That catcher is Willson Contreras. The game is scoreless and there are no runners on base. The hitter is Rodolfo Castro. He’s hitting in the 6-hole in this April 2023 Pirates lineup and has slashed .253/.359/.424 this year. Castro is no 3-0 ambush swing threat. He’s seen nine 3-0 pitches in the past two seasons and has swung at none of them.

So why did Contreras set up in the left-handed batter’s box? I don’t know. I am convinced that targets matter, though. Check out what happened on this 3-0 pitch:

The pitcher (Zack Thompson) hits the lane Contreras asked for. But that target wasn’t in the strike zone, so it’s ball four. Contreras is initially frozen, confused by the call. He turns to the umpire for clarification and asks a yes/no question (my guess: “was that wide?”). The umpire nods: yes, it was wide.

As you watch, you might be inclined to think that Contreras simply forgot where he was. That’s certainly possible, but I’m not so sure. I think this is one example among others of an extreme target-setting approach taken by Contreras this year. I also think this pattern might have had something to do with Contreras temporarily losing his job as an everyday catcher.

News from St. Louis

For anyone who missed it: about a week ago, the Cardinals announced Willson Contreras wouldn’t be catching anymore (at least for a while). The initial news suggested a move to the outfield and DH. The outfield move was then nixed. Contreras has slotted in at DH exclusively since. On Saturday, it was announced that Contreras would be returning to catching tonight.

I won’t dive into the dynamics at play in making this type of move with a player who is one month into a 5-year, $87.5 million guarantee. I am interested in diving into the specific defensive concerns that might’ve motivated such a move. And, in truth, I’ve been wanting to write about catcher targets for some time. Contreras provides a great lens through which to showcase their importance.

Before I jump into a deeper dive into targets, I should contextualize where they fit into the list of catcher responsibilities.

A catcher’s job

If you were to break up a catcher’s defensive skillset into a few buckets, those buckets might look something like:

Throwing

Blocking

Receiving

Game-calling

The first three items on this list are quantifiable, and are not the issues cited in the Contreras demotion. Contreras has a great arm and has a way of finding opportunities to use it. He’s never had an issue blocking balls in the dirt, either. As many catchers have adopted a knee-down setup that is geared toward picking up the extra called strike on the low pitch, Contreras’ more traditional setup has put him in a great position to keep dirt balls in front of him.

Pitch receiving has been a bit of a question mark for Contreras in the past given his zealot-like pursuit of throwing out baserunners. But poor receiving/framing wasn’t cited as a reason behind his demotion; this year, he’s actually ranked in the middle of the pack in strikes won/lost for his pitchers2.

So what’s left? Game-calling. This responsibility is kind of a nebulous one. The literal interpretation is basic: does a catcher call for the “right” pitches at the right time? Can a catcher combine a scouting report with a real-time assessment of a hitter and develop a plan with his pitcher?

We’ve received a few hints from president of baseball operations John Mozeliak about what concerned the Cardinals, and all of these concerns fall into the game-calling bucket. Mozeliak has referenced the “nuances” of the catching position, “preparation,” and “communication between our catcher and our pitchers.” This unquantifiable responsibility is where Contreras needed to make a change.

Game-calling is where targets come into play. We can nitpick on the specific pitch types Contreras has called for, but more telling would be to look at how he’s called for those pitches. Where did he set up? What kinds of nonverbal cues did he use to communicate where he’d like those pitches? What do those cues signal about Contreras’ priorities? Let’s dive in.

Prioritizing the runner over the hitter

If you’re wondering if Contreras cared more about opposing runners or opposing hitters prior to his temporary demotion, look no further than this clip. This is an 0-1 fastball from Zack Thompson to Bryan Reynolds. Ji-hwan Bae is on 1st. It’s the perfect test: attend to one of the game’s best hitters, or try to prevent one of the game’s top burners from taking second base.

Here’s how Contreras sets up:

There’s no question as to where his focus is here. The hitter (Reynolds) may as well not be in the frame. Contreras is set up to throw, and it’s not just the placement of his body (fully outside the strike zone) that tips us off. It’s the angle of his shoulders, too. They’re slanted away from the plate instead of toward the plate.

The effect, to an umpire trying to make a ball/strike decision, is to make pitches on the outer half of the strike zone look like they’re outside the zone:

If Thompson hits this target, the result will almost certainly be an easy take for Reynolds for a ball. But Thompson ignores that target for one that’s in the zone. He throws a pitch at the knees and over the middle of the plate. Contreras has to stab across the plate to grab it. The momentum of this move carries his glove below the zone.

The pitch is called a ball, and Bae (who ran and had a great jump) beats Contreras’ throw. The attention paid to the runner wasn’t rewarded.

Managerial power

That last pitch wasn’t an official pitchout, but it may as well have been. It’s just one example of why you might hear catchers referred to as “on-field managers.” Here’s another one.

The sequence below came in the second inning of a tie game. With two outs and a runner on 2nd, Miles Mikolas has run the count to 2-0. Here are Contreras’ next two targets:

Contreras essentially decides to intentionally walk the Pirates’ 8-hole hitter (Tucupita Marcano). We could debate this decision, but I think I know where we’d land. Obviously, an intentional walk to an 8-hole hitter in the second inning is not a sabermetric-inspired move. That’s not my point here, though. My point is that a catcher can exert even more influence over the game than a manager, just with the decisions he makes about where to set up.

Here’s how these pitches turned out.

The 2-0 pitch sends Contreras diving to his left. It’s not in the zone, but it’s not as noncompetitive as the lunge makes it look:

The 3-0 pitch should be called a strike. But remember that setting a wide target makes it harder to get calls on pitches over the plate. Contreras has to stab at the pitch from his position off the edge of the plate, so the umpire thinks it’s low.

Mikolas walks Marcano on four pitches. While this decision could have come from the bench, I think it’s more likely that it came from Contreras. His targets communicated to Mikolas to punt the at-bat and move onto the next hitter.

Directing traffic with 2 strikes

One last example of the influence that catcher targets can have.

With two strikes (particularly in 0-2 and 1-2 counts), the most disciplined pitching staffs expand. These counts are opportunities to throw your best “waste” pitch - one that doesn’t sniff the strike zone. The ideal pitches to avoid the zone and entice hitters typically aren’t straight. A breaking ball bounced in the dirt becomes a strikeout (at best) or a ball (at worst).

If a two-strike fastball is thrown, the catcher should (with few exceptions) set up to ensure it doesn’t come close to landing inside the zone. With fastballs, pitchers tend to miss laterally more than vertically, so the best target to produce (relatively) risk-free swing and miss is ‘up’ above the zone. When suggesting a two-strike fastball, an advance scouting report might recommend that it’s “higher than high” to ensure the hitter doesn’t get anything he can drive.

The Cardinals allowed 333 two-strike extra-base hits this year heading into May 4th, the date Contreras switched to full-time DH. That total ranks third-most in baseball. As it turns out, St. Louis had also thrown two-strike fastballs more often than all but four other teams in these counts.

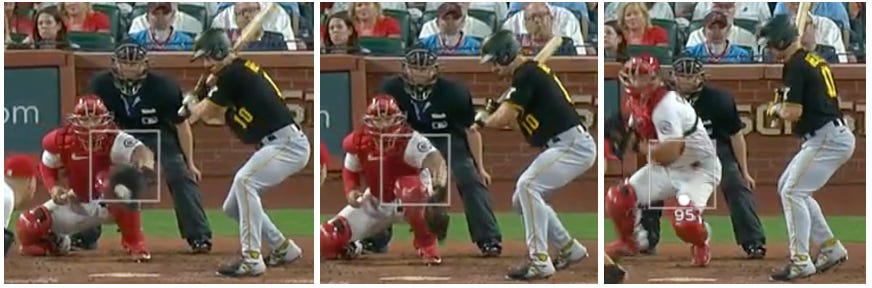

In reviewing these two-strike heaters, I found a bit of pattern in Contreras’ preferred target. It isn’t higher-than-high. It’s this:

In. Contreras likes to go ‘in’ on hitters with two-strike fastballs. Each of the three targets shown above also resulted in extra-base hits.

The first target above (down/in) is pretty hard to justify. That’s where hitters typically do the most damage. The next two targets might not be harmful in a world where every pitcher hits his spots, but not in the real world. In the real world, the up/in target is a difficult one to nail.

And for a pitcher throwing to an opposite-handed hitter (say, a left-handed Steven Matz pitching to a right-handed Teoscar Hernandez), a mis-executed up/in target typically results in a lateral miss - a fastball left over the plate:

So, before jumping on Cardinals pitchers for a “lack of execution” with two strikes, consider the pitches they’re being asked to execute. Those decisions come from their partner behind the plate.

Back to the job he was hired for

When Contreras returns to regular catching duty tonight, a number of different cues will tell us where his focus is. The one-knee experiment4 will be one to watch. Does Contreras embrace a receiver-first approach, even with runners on base? Does he return to a traditional catching setup when he needs to block a ball or throw a runner out?

Beyond the knee or not-to-knee decision, the placement of Contreras’ body and glove will tell us if any significant changes have been made to his approach to calling a game. In just over a month, Contreras revealed the impact that a catcher’s targets can have on managerial priorities, the strike calls his pitcher gets (and doesn’t get), which hitters his pitchers try to attack or avoid, and what pitches those pitchers attempt to execute. Targets matter.

Have a great week!

also in 2022

I think BP’s leaderboard is the best public go-to for all things catcher defense (framing, blocking, and throwing).

2-strike counts excluding 3-2 (0-2, 1-2, 2-2)

Contreras, prior to a change made a few weeks ago to his setup, was one of the few remaining holdouts against the knee-down setup. On/around April 13th, he switched things up. He started dropping to a knee about as often as he used his old setup. The screenshots below are taken two days apart (April 11th on the left, April 13th on the right).

I could be wrong, but this change doesn’t seem like one that would’ve been driven by Contreras. Contreras had tried this in the past but never for long. His entire approach to catching has always appeared to be more focused on antagonizing runners than on helping his pitchers get hitters out (case in point: even after the more-permanent knee-down switch on April 13th, Contreras often popped back into a traditional crouch with runners on base).

![[crop output image] [crop output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nGtJ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F499a7aa4-d1f1-4790-b3fa-61e3c1d2ddf6_153x115.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0s04!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0c98e8c9-60d8-436a-8a20-4d8e1b712cea_256x192.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qdUx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe0187f0e-9d98-477d-b9a3-5de183e63978_254x190.gif)

![[optimize output image] [optimize output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Bx8B!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3a7fe3e4-ab82-449c-b258-a4b7338d3ec3_273x205.gif)

@noah, u got a shoutout on your article and they discussed it over the last 7 or 8 mins if this episode. Thanks for putting out thought-provoking, conversation starting type of material! In case you csnt click the link in this format, it’s the latest episode of “seeing red” which is a cardinals pod hosted by will leitch and Bernie miklasz

https://open.spotify.com/episode/7m1WeCKujd2yfSYgzVE2RP?si=RDW5PvaeSM6jiCbig6bgHQ

You’re gonna get a lot of reads from stl on this! Hopefully a radio or podcast interview or two as well. You’re the first I’ve seen to actually EXPLAIN some of what he was doing wrong, cause lord knows Mo n Oli have not spoken in any specific terms. I think it only hurt them, honestly