Marcus Stroman is not trying to throw strikes

A 90's throwback

A little while ago, a front office staffer asked me if I was a “catcher target guy.”

I asked him what he meant by that question. He posed two possible options:

Should catchers set up down the middle all the time? (the Tampa Bay model)

Or, should catchers set up in the ideal landing spot for each pitch? (the Greg Maddux model)

Obviously, I copped out: it depends on the pitcher.1

Some pitchers (more and more of those coming up through the minor leagues these days) are stuff-over-command; they’d benefit from wider margin for error inside the zone. A down-the-middle target does that by minimizing the distance a catcher needs to reach to snatch a 97-mph fastball that could appear in any quadrant of the zone.

Because Tampa is Tampa, the “down the middle” approach to catcher targets is all the rage right now.

On the other hand, though:

This pitch is an 0-0 sinker from Marcus Stroman to Bo Bichette from two weeks ago2. Stroman’s catcher (Austin Wells) sets up with his glove over the white line of the left-handed batter’s box. Stroman throws a fastball that starts at Wells’ right shoulder and runs across his body.

Wells sets up for a ball. But it’s called a strike.

Stroman is not the prototypical pitcher coming up through the minor leagues these days. He doesn’t throw 97 mph, and he does have an idea of where each pitch is going. This is a ridiculous target and a ridiculous strike call.

It’s his thing

This instance wasn’t the first time I’d seen this type of target from Stroman. The first time I saw it, I assumed it was a Yankee thing.

It might be a bit of a Yankee thing, but I think it’s more of a Stroman thing. See below for a few shots of other Yankee starters (all are 0-0 fastballs). Pay attention to the white reference line drawn above the left-handed batter’s box edge. The glove location is important, but the catcher’s body positioning is also very important:

Yankee catchers will occasionally approach Stroman target territory with other pitchers, but only in specific circumstances. This is not the default mode of operating for any other pitcher on the staff.

Why do this?

Two reasons:

There’s a huge called strike advantage to this setup. If both catcher and pitcher execute, you get a lot of frustrated hitters. After a few calls like the one on Bichette above, you might even goad the opposing manager into starting a long-distance conversation with the home plate umpire:

There’s also an “execution” advantage to this approach. Stroman knows his fastball runs toward a right-handed hitter. So, if he wants to account for that type of movement, an extreme target can help him do that. It’s the same way a golfer might play for a natural fade.

Stroman’s sinker moves a ton. He starts it just outside the target, knowing that it will either:

land safely outside the zone (in the case that it doesn’t move that much), or

if all goes well, work its way toward the outer edge of the plate:

Moving the zone

More on that called strike advantage. We’re familiar by now with the value catchers accrue through stealing strikes. Per Baseball Savant, eight stolen strikes is worth roughly a run saved3. We rank catchers by the number of runs they save in this department.

But we can also use that same lens to examine the other partner in the pitcher-catcher tandem. And guess who ranks #1 in catcher runs saved amongst all qualified pitchers:

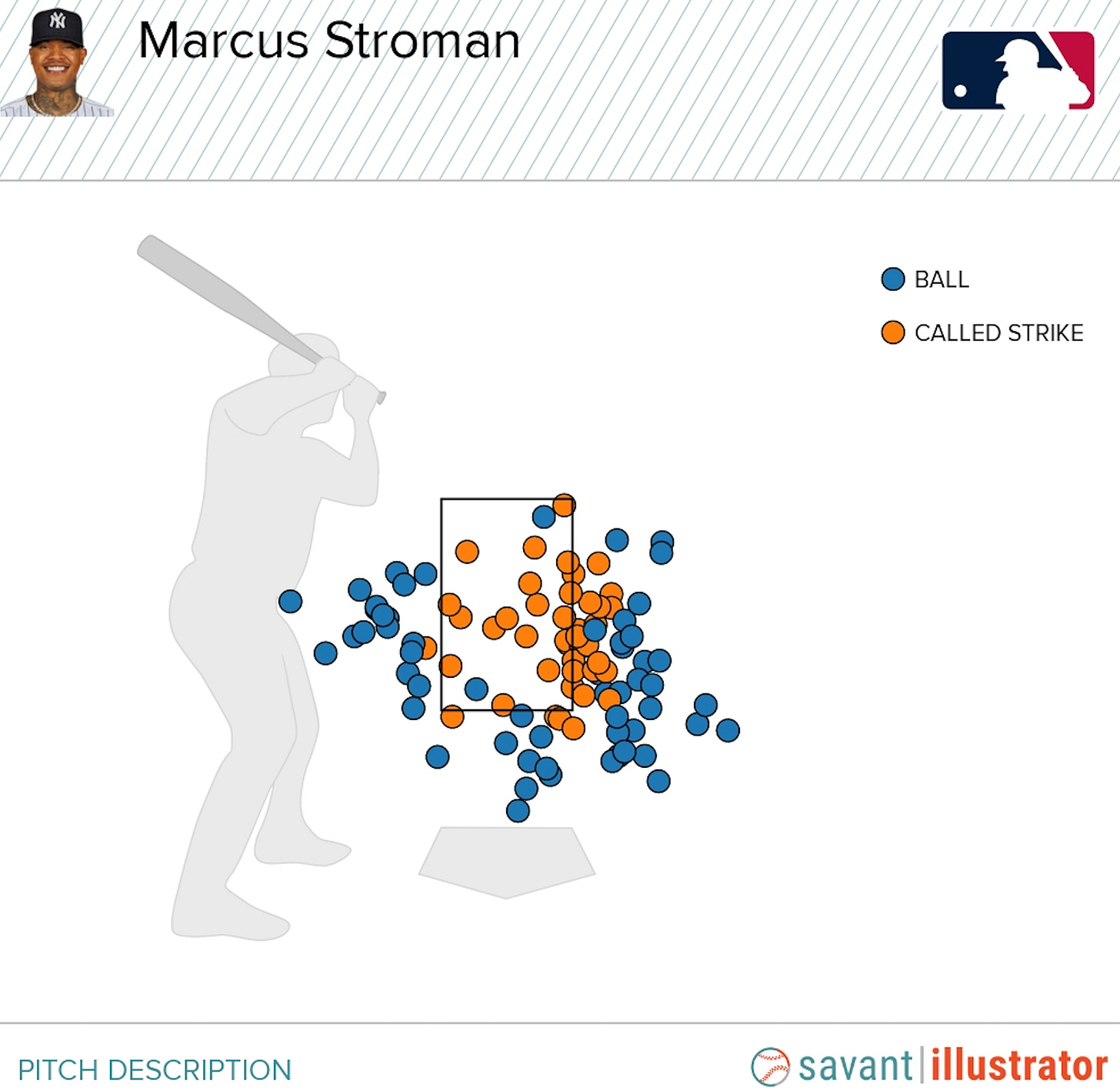

Stroman and his catchers excel across the bottom of the zone and to Stroman’s glove side (away to right-handed hitters):

Most of these bonus calls are on that run-back sinker4. Just look at all the orange dots outside the zone on that pitch:

It’s not just his sinker, though. Here’s a 1-1 slider in the same Bichette at-bat(!) from above:

Tough day to be Bo Bichette. After the sinker and the slider call, Bichette can’t expect that this slider will be called what it is (a ball). So he has to swing at it:

That’s the power of the called strike.

Avoiding danger

That first slider above (the called strike) wasn’t Stroman’s best slider; it backed up toward the plate. But because Stroman gave himself some margin for error, he didn’t leave it in a dangerous place (over the middle of the plate).

Stroman’s approach is about limiting damage. Here’s what he had to say after the start in which he stole strikes from a bunch of Blue Jays:

“Early on in the game, I put a priority on limiting damage and doing as much as I can to keep the team in the game. I feel like this lineup is so potent that they can explode at any time.”

By setting his sights on an exaggerated target, Stroman gives himself room in both directions to miss safely.

Take his breaking ball(s), for example. Pitchers tend to miss along their arm path for a breaking pitch. Pitches that are “hung” (undercooked) will miss high, and pitches that are overcooked will miss low or spike into the dirt. Stroman’s path is highlighted by the yellow line:

When Stroman hangs a breaking ball, some of those misses will end up in the zone. But most will miss in a relatively safe location just off the plate. When he executes a breaking ball perfectly (the middle box), he ends up in a location only he can win in. And while you could question a hitter’s willingness to chase that far off the plate, just remember the example of the frustrated Bichette from above.

Going full Maddux

In July of 1997, Greg Maddux threw a 78-pitch complete game. To complete that feat, all he and catcher Eddie Pérez had to do was move the strike zone one foot further away from right-handed hitters.

Maddux got calls like this one on Sammy Sosa:

And this Stroman-like run-back sinker on Shawon Dunston:

We aren’t living in Greg Maddux’s world anymore. For now, we’re in this middle ground in which umpires are tracked and graded, but still human. Until the zone is fully robot-run, there’s still an opportunity for pitchers like Stroman to play the game. And while going “full Maddux” isn’t for everyone, it’s not a bad idea for pitcher-catcher tandems that can pull it off.

Have a great week!

My simple answer: yes. I’m totally a “catcher target” guy. Last year, I was so moved/put off by Willson Contreras’ targets that I wrote 2,000 words about them.

3rd inning, April 17th

1 strike = .125 runs(ish)

If you want to see for yourself, this search should give you clickable video on each pitch.

This was a fascinating article. Articles like this and your one on the "Exposure effect" of relievers add to the enjoyment of the game that I grew up loving. You have wonderful insights. Thank you for sharing them.